We obviously hope that your prints are perfect and you’re enjoying smooth, vibrant results every time you print! However, if you do notice something off—whether it's a slight wobble in the lines or colours that seem a bit dull—there are common causes behind these print quality issues.

While some issues may be trickier to resolve than others, understanding what could be causing the problem can help!

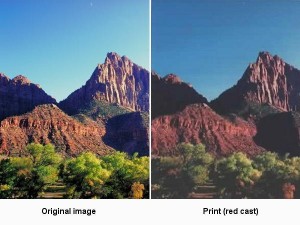

Colour Imbalance

The translation of the colours you see on the screen to those your printer produces is a complex and approximate process. If the algorithms in the printer software aren’t right, you can get imbalances in the colour, where prints can be too rich in a particular shade or shades.

These colour casts are often referred to as too warm if they veer towards the red end of the spectrum and too cold if colours are too blue.

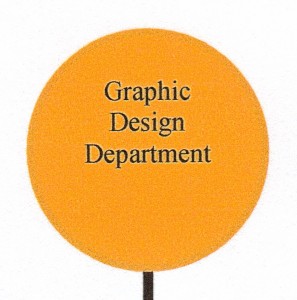

Haloing

When printers are asked to print colour with black on top, such as with text on a coloured background, their firmware does it in two stages. It prints the colour with the text left unprinted , so the white of the paper shows through. The text is then printed in this space, so it’s truly black and not tinted by the colour of the background.

If the black text doesn’t align accurately with the space left for it, the white of the paper shows around parts of the characters, producing little white ‘haloes’.

Feathering

Inkjet ink is a liquid with either a dye or a pigment providing its colour. When the ink hits the paper, particularly plain paper, which has no coating designed to cope with liquid in a controlled way, it soaks into it. If it soaks down into the fibres, it doesn’t have much effect of the appearance of the print, but if it soaks along the fibres, characters, lines and images can look spiky, or a bit like the fronds on feathers, hence the term ‘feathering’.

Inkjet inks are designed to dry very quickly, to try and minimise the time it has to soak into the paper, but some inks do better than others. It’s also a good reason to store your plain paper in a dry place.

Print Swathe Misalignment

Unlike laser printers, which print pages in one continuous movement, inkjets spray a swathe of ink across the stationary paper and then advance the paper before printing the next one. The movement of the paper through the printer has to be very accurate, if you’re not to get gaps between swathes, but the print heads also have to align themselves accurately from side to side, or you’ll see little ‘jags’, where the print doesn’t quite line up.

Draft print modes, where the paper passes more quickly through the printer, often show more of these types of misalignment.

Blocked Nozzles

The nozzles through which ink is sprayed in an inkjet are very small. Inkjet makers build in measures to keep them unblocked, which is why inkjet printers ‘housekeep’ by spraying small amounts of ink onto internal ‘diaper’ pads at regular intervals. Even so, if you leave a printer for a long period without printing, the nozzles can clog, so you have to implement extra cleaning cycles.

The piezo-electric heads in Epson inkjets are particularly prone to this, so it’s best to leave Epson printers in standby mode, where they can occasionally clean themselves, than to turn them right off.

Striping Or Banding

Because laser print involves solid ink, the fine toner powder doesn’t flow in the same way as liquid inkjet ink. Variations in the amount of charge the drum can hold and its consistency can lead to variations in the smoothness of particles on the paper. It shows up most in large areas of grey fill, which can look patchy or blotchy and isn’t easy to rectify. You can ask for print samples before you buy, though, and compare grey fills directly.

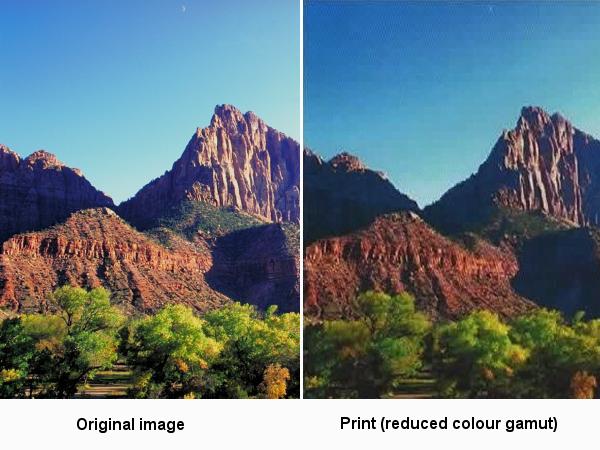

Restricted Colour Gamut

Although colour laser print is improving, it still does much better with graphics than photo images. This is because colour toners have a greater limit on the number of colours they can reproduce than inkjet inks.

Because a printer has a limited range of colours (technically the ‘colour gamut’), it can’t produce every shade that’s called for; it has to use the closest one it can produce. With a smaller colour range to choose from, the shade chosen will be further away from the true one. The result is a gaudy image, sometimes described as ‘picture postcard’, after cheaply printed seaside postcards, which also have limited colour gamuts.

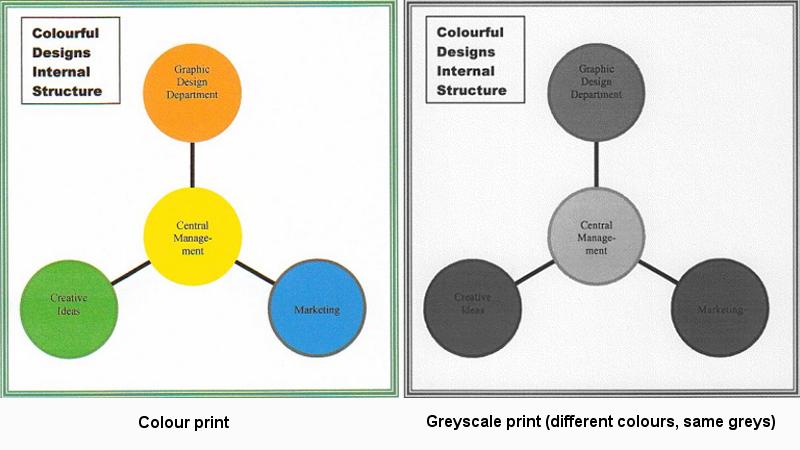

Poor Greyscale Range

This problem is related to the colour gamut restriction, but for mono laser printers. If a printer can only produce a limited number of shades of grey (greyscales), different greys in an original may appear as the same colour in a printout. Most mono lasers claim to be able to reproduce 256 grey levels. Not all can, but an added difficulty crops up when trying to print a graph or chart when the original is in colour.

In translating colours to greyscales, a printer’s firmware only looks at the lightness or darkness of the colour, not at its actual colour. Two completely different colours, say red and green, could have the same lightness and would therefore be printed as exactly the same shade of grey.